Eén van de zaken die de Beurs van Berlage bijvoorbeeld zo uniek maakt is dat het als Gesamtkunstwerk is opgezet. Berlage besprak met de dichter Albert Verweij het beeldprogramma. Daarin zaten twee doelstellingen:

1- het neerzetten van Amsterdam als handelsstad door de eeuwen heen

2- het vooruitwijzen naar de toekomstige klassenloze maatschappij zonder geld.

In feite bouwde de geengageerde socialist Berlage een gebouw voor de handel, vanuit het ideaal dat op termijn die handel er niet meer zou zijn en het gebouw dan een tweede leven als gemeenschapshuis zou kunnen gaan krijgen. De architectuur modelleerde hij dan ook naar de middeleeuwse raadhuizen van Italiaanse stadsrepublieken (Palazzi del Populo) waarin een duidelijke rol voor het volk was weggelegd. Maar je zou ook zomaar kunnen zeggen dat het op allerlei manieren een Occupy-statement avant la lettre was.

De buitenkant: beursplein?

In de gevel van het pand, aan het Beursplein zijn beide doelstellingen te herkennen. Helemaal bovenin de gevel zien we het wapen van de stad Amsterdam (de twee mannen in een boot) en iets daaronder een gevelsteen van Lambertus Zijl met drie delen: Het paradijs (links), het Verdorven Heden (rechts) en de toekomst (midden).

De binnenkant: tableaus verleden, heden en toekomst

Als u zich voorstelt dat het cafe aan het beursplein er niet was en ook de toegangen niet waren afgesloten, dan heeft u een beeld bij de ontmoetingsruimte waar de handelaren elkaar tegenkwamen. Ze verzamelden zich bij de diverse tableaus van Toorop. Maar dat waren niet zomaar tableaus: ook hier bleek een visie op verleden (slavernij: vrouw wordt geruild tegen zwaard):

In het heden van destijds (1903) zagen we een klassemaatschappij terug, uitgebeeld door arbeiders enerzijds en directeuren anderzijds:

En rechts daarvan zagen we het eind ideaal. Geen klassenmaatschappij. De oude arbeider rechts bergt zijn spullen op en ziet toe hoe zijn kinderen gezamenlijk dansen in een tuin waar man en vrouw gelijk zijn.

De hand en geldzak tussen twee beurzen

Ook in 1903 was er al het besef dat je met geld eervol moest omgaan. Om de handelaren daaraan te herinneren was er tussen de Koopmansbeurs en de zaal voor de Effectenbeurs een geldzak te zien , met daarboven een hand. De hand had de vorm van een hand die een eed zweert. Deze morele oproep werd echter weinig gewaardeerd door de handelaren en de hand/geldzak werden verwijderd.

Gauw verhuizen dus....

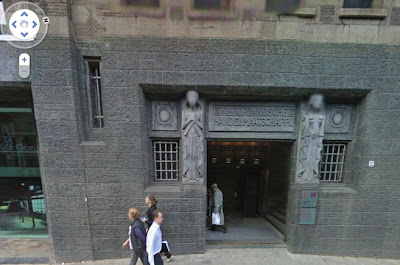

Het zal niet verwonderen dat met deze overdaad aan symboliek (en, dat moet gezegd: de beperkte ruimte en de gebrekkige verwarming in de Beurs van Berlage) de effectenhandelaren na verloop van tijd gingen omkijken naar een nieuw gebouw. Toen het contract afliep en hun portemonnee na een aantal florissante jaren goed gevuld was, kochten de handelaren het Bible Hotel aan het Beursplein op om op die plek een mooi gebouw te laten bouwen, zonder al te veel socialistisch-idealitische symboliek.

Meer daarover een andere keer.....